On what must’ve been my six or seventh birthday, my dad gave me the late-80s version of the Cadaco All-Star Baseball. If you played it as a kid, you might know it as “the spinner baseball game.” It’s the one where baseball player’s faces were printed on discs, with the outer part of the disc divided up into 14 sections. Each of the 14 sections represented an outcome based on that particular player’s baseball career (1 was a home run, 2 was a groundout, 3 and 4 were flyouts, five was a triple, and so on). In the late 80s version of the game, you would place the disc into a plastic sleeve with a spinner on the outside, flick the spinner, and use it to simulate a baseball game.

I loved this game. I would play whenever I had a chance, with my dad, with my brothers, with my friends, with whoever would tolerate me. The problem that I always had was this: my brothers were too little to really appreciate the game, my friends didn’t like baseball nearly as much as I did, and my dad only had so much time on weekends to really dedicate to massive, sprawling series of games that I wanted to play. At some point after giving me the game, my parents sent me and my brothers down to my grandparents’ house for a weekend. Before I went, my dad told me that I should tell my grandfather how much I loved the spinner baseball game.

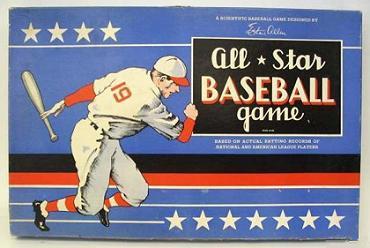

When we got to Murrysville, I told my grandfather about the spinner baseball game and how much I loved playing it. He took me down to the game closet in their basement, and pulled out a battered old box that was barely held together by numerous tapings and re-tapings. The top of the box said simply, “All-Star Baseball Game.” Inside, it was full of the same discs I knew from my game at home. They were older than mine and yellowed, they didn’t have player’s faces on them (instead, there was a rounded rectangle cut out of the middle to fit a block under the spinner), but I saw the number pattern and recognized them immediately. There were actually two kinds of discs in the box; the thin, papery discs featuring the stars of the 1960s that belonged to my dad and his brothers during their childhood, and the thicker, cardboard discs featuring players from the 1940s that must’ve been my grandfather’s.

To this young version of me, that box couldn’t have been more valuable if it was full of gold. My grandfather and I immediately started separating the players out by position and drafting our teams. Within a few games, he’d drawn out a meticulously-lined scoresheet by hand and then ran off copies on his Xerox machine. We’d always play best-of-7 series; there were enough discs so that we could have three or four separate lineups apiece. After three or four games into the series, we’d have to start mixing and matching, trying to put our best lineups together for the last few games. We called almost all of our series The World Series; in most of them, I’d be the Pirates and he’d be the Indians.

I have no idea how many games we played. For a couple of years, every time my brothers and I would visit my grandparents, my grandfather and I would go straight to the basement, get the game out, and then start drafting and spinning. By the end of those weekends, I’d have a dent in my middle finger from flicking the spinner so many times; sometimes it hurt so badly that I’d have to start switching fingers as the weekends wore on. I never cared; every single game was a chance to draft a new team, play with them, and hear my grandfather’s stories about the players on the discs. His favorites on the old discs were from the Indian teams he’d love as a kid; most of his stories were centered on Bob Feller, his favorite player. On the newer discs, he could tell me which players were my dad’s favorites and which ones were favorites of my uncles. I was a sponge, just sitting in the basement, soaking up every word of every story. To this day, I still associate a lot of old baseball names with those discs. Ralph Kiner’s massive home run slice was one of the first things I thought of when he died. Recently I saw Bobby Doerr’s name pop up in the news and immediately visualized his card; it was one of the thick, cardboard ones.

Eventually, our games slowed down and stopped. My brothers and I stopped spending full weekends in Murrysville on our own when we got old enough to look after ourselves, and my grandfather’s bad knee made it harder for him to go up and down the steps to the basement where we always played. A few years after we stopped playing regularly, though, my dad gave my grandfather a framed copy of the 1948 Indians’ team picture — the picture itself is sepia toned, but Bob Feller signed the original photo in a bright blue marker right under his name. My grandfather hung it in the basement right near the spot where we had always played our games, and every time we’d go visit them, I’d see it. We never talked about it, but I always thought that he hung it where he did because of all the time we’d spent in that exact spot, flicking the spinner, talking about the history of baseball.

My grandfather died on Thursday morning at the age of 85. At his house yesterday afternoon, my cousins and aunts and uncles and I passed around his obituary, read it, teared up, and nodded approvingly, one by one. After everyone had seen it, my grandmother picked it and read it and said to me, “It’s so unfair, Papa Don was so much more than a few sentences on a page.” That’s how I feel about this post; it’s incomplete, it’s just one nice story about a man that meant countless things to so many people. Papa taught me how to tell stories, though, and so I know that if you tell a story the right way, that maybe the content of it doesn’t matter so much. The point gets across.

Before this weekend ends, I’m going to find a moment to slip away to the basement for just one quiet moment away from the amazing family that my grandparents started after meeting on a blind date almost 65 years ago. Once I get down the steps, the bookshelves on my left will be full of the books my grandfather used to teach himself German after he retired from Westinghouse in the 1990s. In the far back corner of the room, I’ll see the wooden cabinet full of documents from his time as a patent attorney there on the periphery of my vision. I’ll walk past his reading chair and if I look hard enough, I’m sure I’ll find a book or two about the Civil War. Just past that on the wall will be the picture of the 1948 Indians and Bob Feller. That’s where I’m going to stop. That’s where I’m going to take a moment to breath in and let the whole room wash over me, the stories, the spinner baseball game, and everything else. My grandfather lived a life worth aspiring to. I’m going to miss him.

Image credit: Baseball Games’ page on Ethan Allen’s Cadaco All-Star Baseball