Edinson Volquez had a better year in 2014 than he did in 2013. This seems like an obvious statement to make — Volquez had the worst ERA among qualified pitchers in baseball last year, putting up a 5.71 ERA with the Padres and Dodgers. Given that the Padres and Dodgers both pitch in pitcher’s parks, that number is even more impressive. In 2014, Volquez has been the mainstay of the Pirates’ rotation; his 192 2/3 innings are more than 30 more than Francisco Liriano, and his 3.04 ERA is the second best among Pirates that have pitched more than 100 innings. In a season in which the Pirates had trouble scraping five starters together, Volquez took the ball pretty much every fifth day and he gave the Pirates a solid start more often than not.

Here’s the thing, though: if you were to just look at Volquez’s peripherals, you might have a hard time figuring out why he was better in 2014 than he was in 2013. Sure, he dropped his walk rate way down this year (from 4.1 BB/9 to 3.3, or from 9.9% to 8.8%), but he dropped his strikeouts down just as much (7.5 K/9 to 6.5, or 18.3% to 17.3%). His home run rate dropped (1.0 HR/9 to 0.8) and his groundballs ticked up to just over 50% after sitting down around 47% last year. The net effects on his FIP and xFIP, though, were negligible. Last year Volquez had a 4.24 FIP and a 4.07 xFIP. This year those numbers are 4.15 and 4.20.

I’m not particularly interested in dismissing Volquez’s season as a fluke of luck that bounced in favor of the Pirates, nor am I trying to argue that the Pirates have no chance in Wednesday’s Wild Card Game solely because he’s the one pitching it. It’d be one thing to use FIP and xFIP to dismiss Volquez’s results this year out of hand if Volquez had the same rate stats in 2014 as he did in 2013, but he didn’t. Volquez did, in fact, change something this year, and that swung his results even if it didn’t swing his peripherals. That’s interesting to me, and obviously that’s worth exploring with Volquez starting on Wednesday.

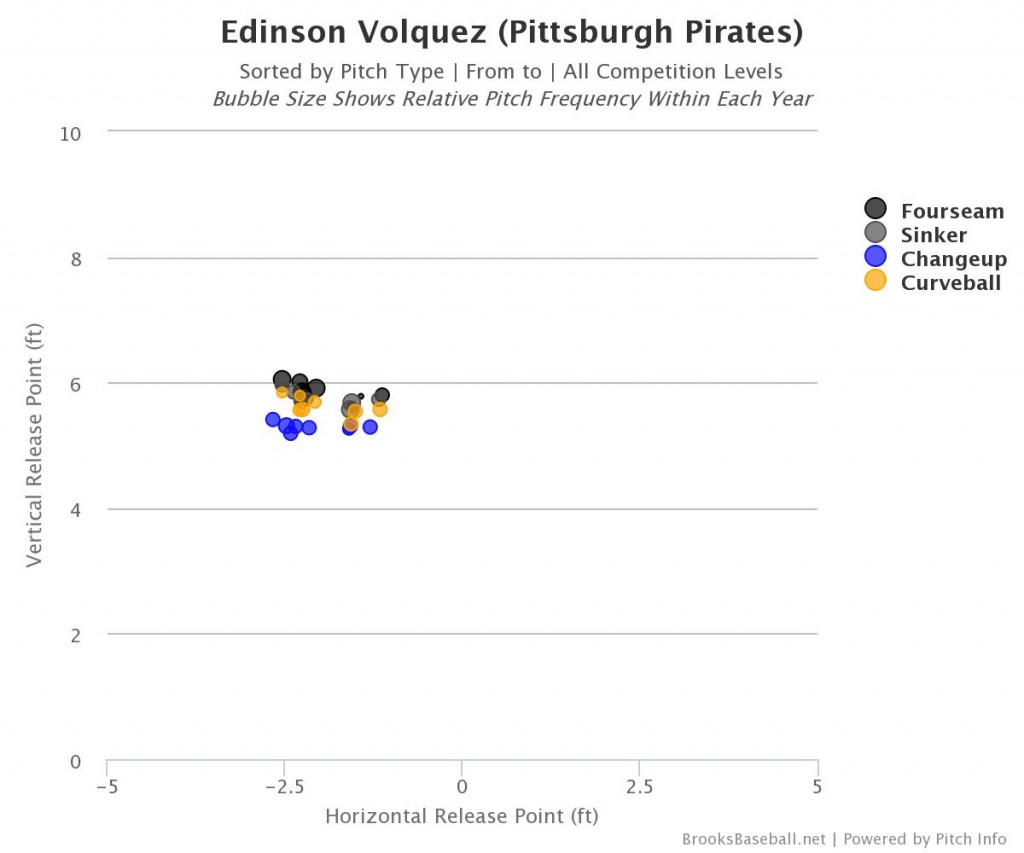

Before the season started, I wrote a long post about what the Pirates could do to fix Volquez, and my two main thoughts were that they could improve the consistency of his delivery and work on the release point of his changeup, which often seemed to be different from the release point of his other pitches. From Forbes to Federal already has a great post up addressing most of the issues I raised in that post from the spring, and you should go check it out now if you haven’t seen it yet. The Pirates clearly did some work with Volquez’s mechanics to straighten them out, and I’m sure that that’s where the improved control comes from. I see one other thing in there that FFtF didn’t notice (which isn’t a criticism: I only see it because I wrote that post in the spring and was specifically looking for it): Volquez dropped the release on his curveball to hide his changeup better. In case you can’t quite see what I’m talking about, here are Volquez’s release points on all of his pitches from 2007-2013. You can see that the changeup clearly comes from a lower release point than his fastball and curveball:

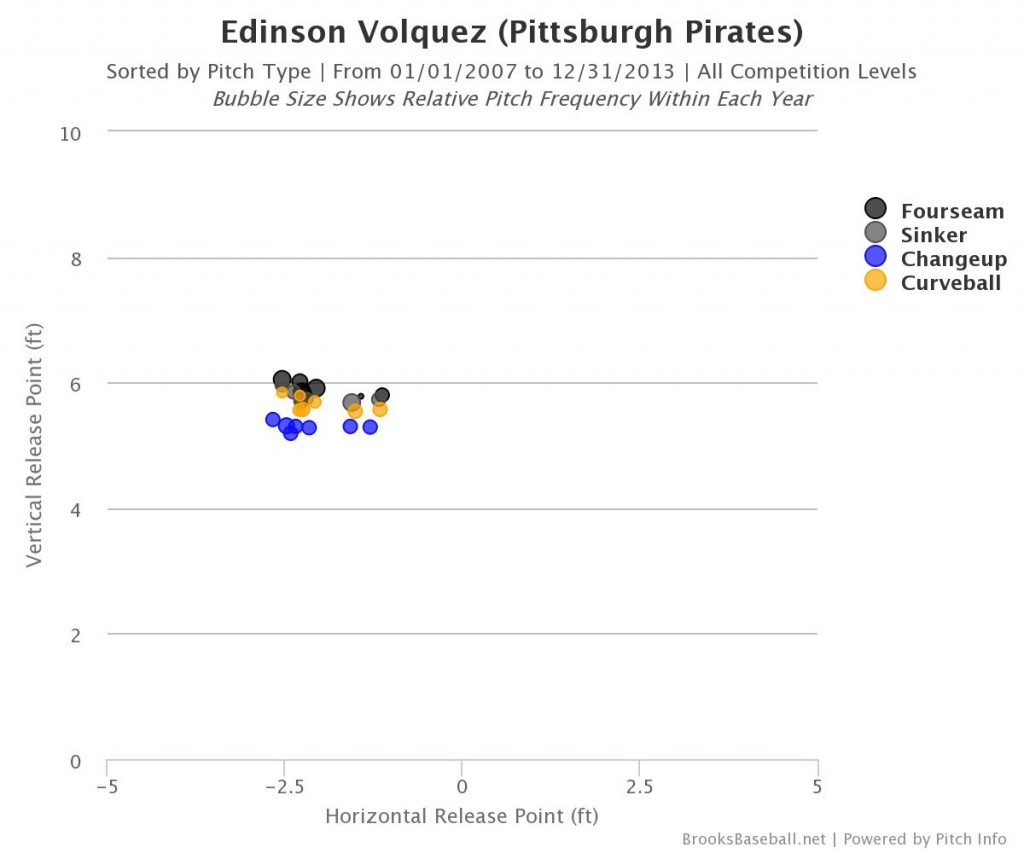

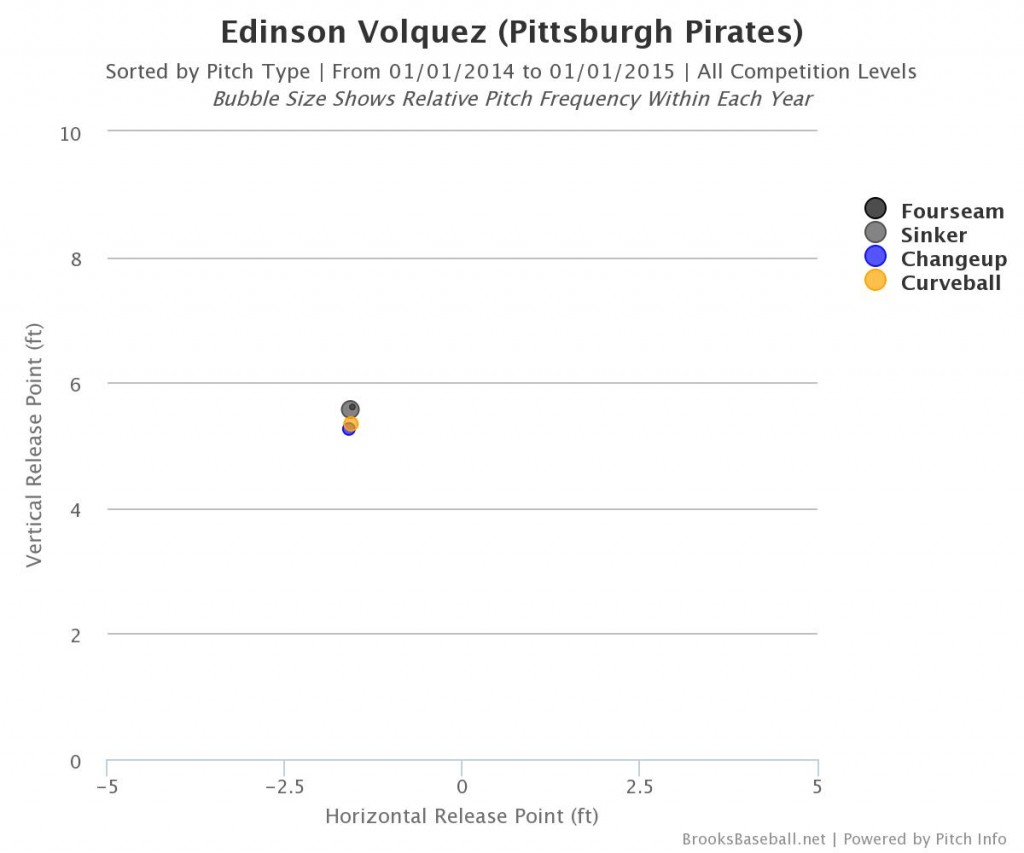

And these are his release points from 2014. See how they blend together a bit better?

If we put them all together, you can see the difference is that he’s dropped the release point on his curveball to match and help blend the changeup.

Now we can mosey on over to FanGraphs and see how that’s changed his pitches this year. Last year, his curveball was an awful pitch, worth a run less than the average curveball every 100 pitches. This year, his curveball has been above average.

Now, Volquez’s curve is an interesting pitch. I’ve talked quite a bit before about how the Pirates seem to love curveballs, and while that statement is true, I’m not sure that it was complete. Brooks Baseball has this cool new beta feature on their landing page where they describe the results generated by each pitcher’s pitch, and this is what it says about Volquez’s curve: His curve has a sharp downward bite, is slightly harder than usual and results in somewhat more groundballs compared to other pitchers’ curves. Guess who else has a hard curve that generates more groundballs than most other pitchers? Gerrit Cole, AJ Burnett, Wandy Rodriguez, and Jeff Locke (I checked a few other pitchers randomly to make sure that’s not the case for everyone, and it doesn’t seem to be). You can also see that Volquez’s curveball usage peaked this year (though it’s been on an upward trend for a while).

You can see from this chart that Volquez’s pitches didn’t change much, in terms of break. You can sort through his usage tables from 2013 and 2014 to see that while the Pirates’ probably tweaked Volquez’s fastball some this year to make it into more of a sinker, they didn’t make a significant change in his approach to hitters. Volquez is throwing the same pitches in the same spots as he did last year. The difference is that he’s repeating his delivery better, and he’s hiding his changeup by moving the release point of his curveball some. There’s value in throwing strikes and disguising pitches, of course, but it’s really hard to find anything dramatic at all in what the Pirates did with Volquez in terms of his individual pitches or approach.

Now, if we go back to ERA it looks like you could break Volquez’s season in half just as easily as you could break his career into “everything before 2014” and “2014.” Due mostly to a serious home run problem, Volquez had a 4.67 ERA through 15 starts after getting crushed by the Reds on June 18th. In his last 17 starts, he had a 1.85 ERA. The Pirates won six of his first 15 starts and Volquez went 4-6. The Pirates won 12 of his last 17 starts and Volquez went 9-1. Again, though, the peripherals don’t change a ton. In those first 15 starts, Volquez struck out 59 and walked 31 in 86 innings (6.2 K/9, 3.2 BB/9, 1.9 K/BB). In the last 17, he struck out 85 and walked 43 over 111 2/3 innings (6.9 K/9, 3.5 BB/9, 2.0 K/BB). The only thing that shifts significantly is his home run rate: he gave up 11 in his first 15 starts and six in his last 17. His groundball rate didn’t change, though (Baseball-Reference lists a GB/FB ratio of 1.12 in his first 15 starts and 1.13 in his last 17), and that crazy home run rate in those first 15 starts was due in part to some Yankee Stadium inflation (he served up four there on May 17th). I’m trying to find a change in his pitch usage pattern at mid-season, but I’m not sure I see that, either. In effect what I’m telling you is this: there are zero indicators that Volquez did much of anything differently between his “bad” first half and his “excellent” second half, even though he more or less stopped giving up runs. This is the sort of thing that gives pretty much anyone with any base of sabermetric knowledge straight-up nightmares.

Now, I do have a bit of a hypothesis about Volquez’s success, as it ties to the Pirates and their general ability to get more out of certain types of pitchers than might be expected. Because the Pirates talked quite a bit about shifting to the pitcher and not the hitter earlier in the season — implicitly they were saying that their pitchers were missing their spots, and that’s why the pitching staff looked so bad –, my hunch is that the Pirates love those hard, groundball-inducing curve balls for a reason. Without having the hard evidence in front of me, it makes some sense that a curveball that tends to produce grounders will herd hitters into a smaller range of likely results than a fastball that tends to produce a grounder. I’m guessing that the work to change the release point on Volquez’s curveball to mask his change-up was as much about the curve as it was about the changeup. If you want to be as optimistic as possible about Volquez (read: if you want to shoehorn the mid-season ERA change into an explanation that makes you feel better about Volquez), then you might be able to convince me that after the Pirates nailed down Volquez’s mechanics, they worked on general strike-throwing before they worked on refining his command, and it wasn’t until his command improved that they were able to really fit the defense in behind him.

I’m going to close by reiterating that pitching Volquez won’t necessarily keep the Pirates from winning on Wednesday. He’s been a perfectly serviceable starter for them this year, and he’s even capable of the occasional gem. His last start against the Braves was phenomenal, his start against the Marlins in August had an even better Game Score, and his complete game against the Cardinals just before that was great. My main concern is that he’s only two starts removed from a five-walk performance against a Cub team that has the patience of a puppy that’s not quite house-trained, and that in just about every other start he’s always good for two or three walks and usually only about five strikeouts to balance that out. I’m happy to admit that Volquez is a better pitcher than I thought he’d be for the Pirates and that he’s probably a little better than his peripherals indicate, but I’m also concerned about how a good team would take advantage of him on a bad control night, because he no longer has the swing-and-miss stuff that’s the best cover for bad control. I know that he hasn’t laid an egg in a while, but I think that a lot of that is due to the Pirates’ schedule. I’ll point back to Volquez’s game log one last time. Volquez is on a good run, but there are a lot of unimpressive teams in the second half of his season.

In other words, Volquez is the one thing that I’m the most nervous about going into Wednesday’s game, and nothing that I found in the process of writing this post has made me feel much better about him starting.